John Campbell Atkinson

Flight Sergeant, the pilot and captain of the aircraft.

Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve 778335

John Campbell Atkinson was born in the northern mining town of Messina (now Musina) in South Africa, on the 28th of October 1918. The town is about 15 miles south from the border with Zimbabwe (formerly Southern Rhodesia). He attended Milton High School, Bulawayo, in Southern Rhodesia. The school still retains the memorial plaques dedicated to alumni who had fallen in war and conflict and John's name can be found on one of these plaques. We managed to contact Robert Franks, who was a near-contemporary of John's at Milton. According to Robert, John was a keen sportsman, gifted and an achiever, he was ever popular and respected by his fellow students. John was also a fluent speaker of Sindebele which is the language of the Ndebele people of Zimbabwe. He would often have his friends rolling in laughter as he mimicked, or performed impressions of the local people they knew.

Milton High School

His father Bertie was born in Bristol in 1879 to Samuel and Jane Atkinson. Samuel Atkinson is described on the marriage certificate as a rag merchant. Bertie had four sisters and a brother, Philip, who died in World War I. At the age of 12, Bertie ran away and stowed away on a sailing ship bound for Canada. He served with the Canadian armed services in German East Africa and ended up in Pretoria, South Africa, where he met Helen Watson Campbell, then a cook in the household of the Rt Rev. Michael Furse, Anglican Bishop of Pretoria. They married in May 1916. Helen Campbell was one of three siblings born into a family of farm workers in Carluke, Lanarkshire, in 1886. John's older sister, Rose, was born in Pretoria in 1917. A year after John was born the Atkinsons moved to a farm in Matetsi, about 45 miles south of Victoria Falls. A severe drought forced Bertie Atkinson to sell the farm and go mining. He died in an underground accident in Jessie silver mine in Gwanda, near Bulawayo, in April 1929. Helen Atkinson moved to the coal mining town of Hwange (then Wankie) and became the proprietor of a boarding house. She died of cerebral malaria in 1935.

John with his mother and his sisters Rose and Helen.

Oxcarts crossing a river much the same as they did the Matetse in the prewar period.

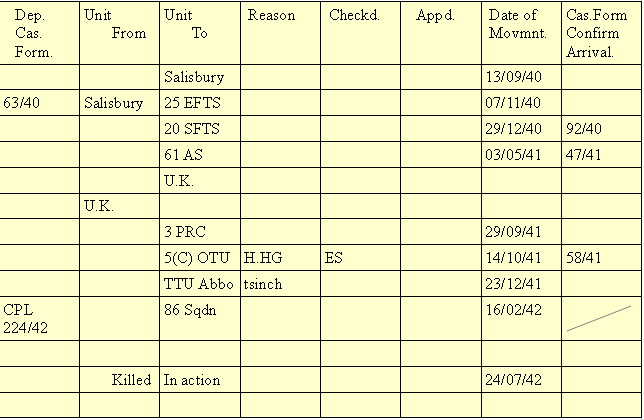

It was in Hwange in the same year that John Atkinson became an apprentice electrician and a keen amateur footballer with the colliery. John completed his apprenticeship in time to be sent to Bulawayo on military service. He was accepted into the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve in September 1940 through the Empire Air Training Scheme and the Rhodesian Air Training Group in Salisbury, the capital of Rhodesia. In November that year he started his pilot training at the 25th Elementary Flight Training School in the Salisbury suburb of Belvedere. The role of 25 EFTS was to bring pilot cadets up to "wings standard" through basic flight training on De Havilland Tiger Moths, Fairchild Cornells and North American Harvards. This was a course that normally took 12 months to complete. John completed his pilot training well ahead of schedule. He graduated in December that year and was posted to the 20th Service Flight Training School (20 SFTS) at RAF Cranborne, Salisbury, to train on Harvards and twin-engine Airspeed Oxfords.

The de Havilland Tiger Moth was the most widely used basic trainer.

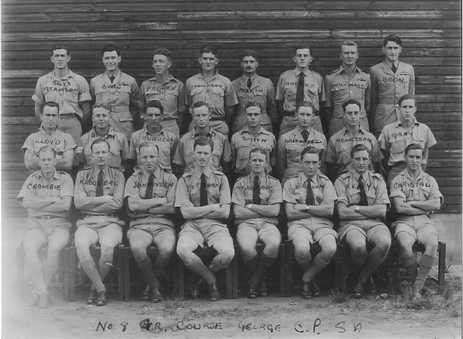

In May 1941 John was sent to the 61st Air School SAAF at George on the South African south coast, which conducted maritime reconnaissance training on the Avro Anson, a twin-engine aircraft that was considered obsolete for front-line service but saw widespread use as a trainer. He told his sister Rose in a letter dated 22 May 1941: "Yes, I have finished my advanced flying training and they have now sent me to George to teach me to be a pilot navigator in the Coastal Command and one of these days if all goes well [I] might be captain of a Sunderland flying boat or Lockheed Hudson." It would appear that John's career path had been predetermined by this time and Coastal Command were in desperate need of strengthening to combat the heavy loss of allied shipping to the U-Boat wolf packs in the Atlantic as well as Britain's coastal waters. 61 AS conducted maritime reconnaissance training, which included sea navigation using “Dead reckoning” and astro-navigation. Ship and aircraft recognition featured heavily during this part of the training programme and the pilots and aircrews would be able to guess quite easily their eventual destinations after completion of their courses simply by which ships and aircraft they had to learn to recognise. It was at George that John first met Allan Hurrell and Cliff Thompson with whom he was to attend the same training courses and be posted to the same squadron. They carried on flying together until Allan and his crew were shot down in an attack on the Prinz Eugen, a German battle cruiser, in May 1942. Allan was the only survivor and was taken prisoner. John's and Cliff's crews returned safely to base.

John with Allan, Cliff and their fellow students at George.

Having completed their training in South Africa, John, Cliff and Allan traveled to England from Durban on the Canadian troopship RMS Empress of Australia... via Canada. The voyage was not without incident - the ship's crew went on strike in the middle of the Atlantic! He reported at the 3rd Personnel Reception Centre (3 PRC), Somerset House Hotel, Bath road, Bournemouth on 29 09 1941. This hotel dates back to the 1860s and had been procured for, or by, the Air Ministry. It is still in business and is now known as the Mayfair Hotel. Its main use was for the barracking and temporary accommodation for some of the many thousands of freshly trained allied airmen arriving from all over the world. This was due entirely to the success of the Empire Air Training Scheme. These men were generally awaiting further training courses or assignment to a squadron or aerodrome and would have had to remain at the reception centres until their next orders or postings were issued. There are a few accounts of other PRCs being sparsely decorated and poorly equipped, cold, damp, overcrowded and uninviting places. Ill-suited for this important purpose, with very limited services and virtually no staff, the conditions left many servicemen desperate for their next posting. According to Allan, conditions at Somerset House were quite comfortable.

Fortunately for John Campbell Atkinson, he had to only "endure" 15 days at the most with 3 PRC as he arrived at No. 5 Coastal Operational Training Unit (5(C) OTU) RAF Chivenor in north Devon on 14 10 1941. During his 5 or so weeks at Chivenor John would have learned to fly the Beaufort. He would have needed time to familiarise himself with the flight characteristics and and capabilities of the 4 man aircraft as well as learning its limitations and emergency procedures, all whilst working for the the first time with three other guys making up the crew. The original plan was to merge 5(C) OTU with 17 Group at RAF Turnberry in Scotland, and train the aircrews there. However, the airfield or runway could not be finished in time, so Chivenor was selected and, taking over the Beauforts of 3(C) OTU, reformed on 01 08 1941 with Ansons, Oxfords and Beauforts. RAF Chivenor and Coastal Command followed Bomber Command's methods of “crewing up” their aircraft, with the new airmen all put into a hanger and left to “get on with it”. Soon, groups of men would walk from the hanger as a crew. According to Allan Hurrell, the gunners tended to be paired off already because they had trained together and already knew each other. They then hunted down a suitable pilot and observer to join them. The crew's observer at this time was a man named Everett - he wasn't posted to 86 squadron with the others for reasons unknown. According to Allan, Everett was something of an oddball who didn't really fit in socially. Two months later they were sent to RAF Abbotsinch (now Glasgow Airport) for torpedo training. The Torpedo Training Unit (TTU) at Abbotsinch was where the Beaufort crews perfected the delivery of the aircraft's primary weapon - the 18" Mk XII torpedo. Practice or dummy ordnance was used during most training. Opened for torpedo training in 1940, the TTU trained both RAF and RNAS crews. Eventually being handed over to the Royal Navy entirely in August 1943, and renamed HMS Sanderling. The majority of the training took place on the river Clyde. The successful deployment of a torpedo required the pilot to fly straight and level at an altitude of 20 metres at 150 Knots for about a minute prior to release, making the aircraft very vulnerable to flak during the attack run. This tactic was forced by the tendency the torpedo had to break up on impact with the water if it was released at the bottom of a dive as it had been with the Beaufort's predecessor. The practice torpedoes were made of wood, weighted and banded in steel. One of these is on display at the Royal Naval Air Service/Fleet Air Arm Museum at Yeovilton in Somerset.

On 16 February 1942 John and his friends joined 86 Squadron Coastal Command at RAF Wick, near John O'Groats; he was 23 years old. In a letter dated 24 April 1942 to his sisters Rose and Helen, John wrote: "I have been on the Squadron over two months now and I hope my luck holds - we have been all over the place in that time. I have been promoted to Flight Sergeant, so in future kindly address yours truly as such!"

From March to June of 1942 John and his crew flew a total of eight missions including the ill-fated attack on the Prinz Eugen. All of the other missions were primarily reconnaissance missions with the exception of a strike mission against the German pocket battleship Lutzow, which was unsuccessful because they were unable to locate the target.

86 Squadron was due to re-equip with Consolidated Liberators for maritime patrol duties in the autumn of 1942. In preparation for this they were reduced to a cadre with the majority of the aircrews flying their Bristol Beauforts out to Malta via Gibraltar where they were to be used to attack the convoys carrying supplies to Rommel's Afrika Korps. The aircraft were flown to No. 1 Overseas Aircraft Despatch Unit at RAF Portreath in Cornwall where the crew rested for a week (due to the lack of accommodation in Gibraltar) before taking off. Cliff and his crew did successfully reach Gibraltar and, eventually, Malta. They were later shot down and taken prisoner by the Italians; Cliff survived the war.

The following account of John Atkinson's time with 86 Squadron is given in an extract from a typed, undated letter found in a folder of the late Helen Francis, John's younger sister, in 2012. It's not clear how it came to be in her possession. The sender's name is unreadable; the recipient appears to have been Mrs Mimi Button of Wankie, a friend of the Atkinson family: "While I was in London I saw quite a bit of John Atkinson. He is very fit and sends his regards. He is flying Bauforts (sic) - after shipping mostly. He was on the "Prince Eugen" show for one. He is doing dangerous work and has had one or two close calls lately. He asked me to tell you this. If he goes for a loop, he wants you to tell the folks at Wankie that he has tried hard and done his best and that he will be thinking of them all. I did not like it very much and tried to laugh it off but he was very serious. I've been hearing tales about John too. He is making quite a reputation for himself and is a grand and daring pilot. Always goes in on an attack but usually gets home again somehow. I hope he comes through O.K. He is a grand chap."

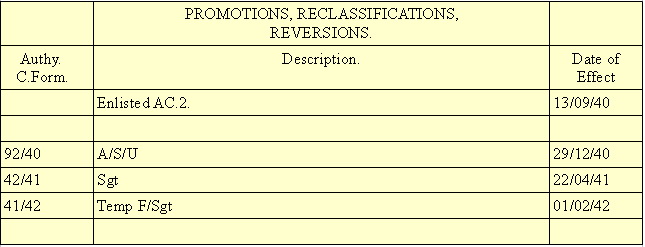

Extracts are from John's service record.

AC.2. - Aircraftsman 2nd Class.

A/S/U - Acting Sergeant Untrained.

John's's gravestone in Illogan Cemetery